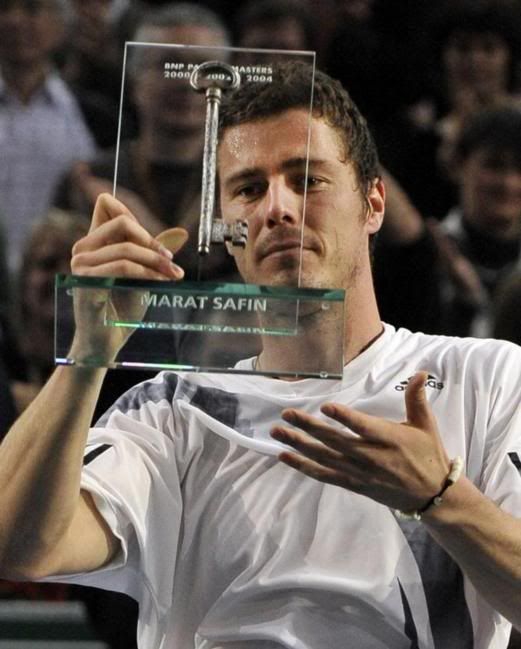

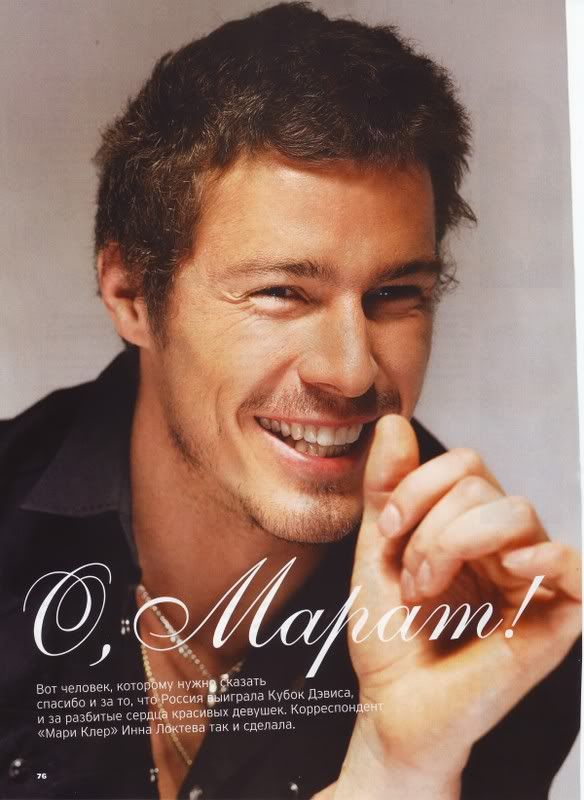

Marat's Apartment and

Article by Justin Gimelstob

Article by Justin Gimelstob

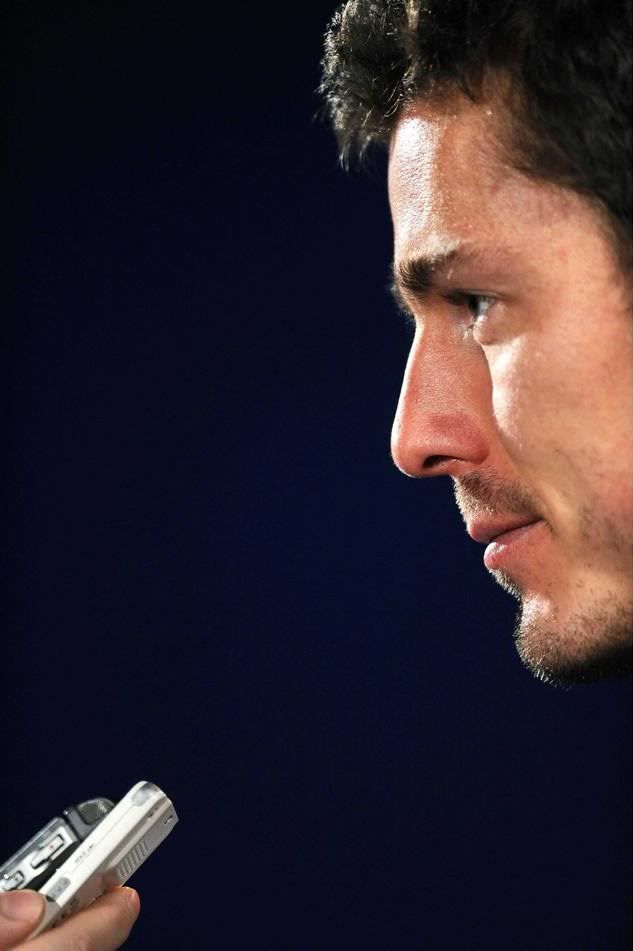

Former ATP pro Justin Gimelstob profiles the legacy of Marat Safin, one of the

most charismatic and complex tennis personalities in recent years, who retired

from professional tennis in November.

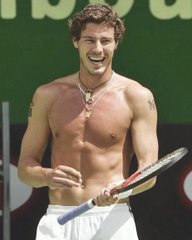

Tennis is a sport that challenges its participants with two competing extremes. In order to be successful, a player needs to simultaneously maintain both heightened intensity and detached calm. It is an elusive balance that ironically lures perfectionists to a game that cannot be perfected. Marat Safin embodies that dichotomy. There has never been a player who has made the game look so easy externally while internally being at such odds with his emotions and mind.

When Safin burst onto the ATP World Tour in 1997, it was with both an explosive game and temperament. Neither subsided throughout his career. Safin was in a lot of ways a pioneer of playing styles, a hybrid between physical dominance and technical efficiency.

In 1997, Safin played his first Kremlin Cup and lost a third-set tie-break to savvy veteran Kenneth Carlsen. Talent dripped from his body more profusely than sweat from the rigorous match. He was a combination of speed and natural power, the type of power that came with fluidity, not brute force. Safin's red Head tennis racquet looked small in his hand, like a twig he was flinging through the air. He strutted around the court with his now customary swagger, torpedoing balls with complete disregard to the score and occasion that underlined his high expectations

A few weeks ago, after Safin played his 12th and final Kremlin Cup – a typical Safin tournament with highs and lows – the former World No. 1 readily admitted that he had not achieved tennis perfection. Of more relevance is the question of whether Safin maximised his talent, which many fans think should have yielded far more than two Grand Slam championship titles.

In a first round upset of his compatriot Nikolay Davydenko, Safin still had the signature two-handed backhand that, when he lowered his shoulder, sounded like a thud echoing throughout the giant stadium. His footwork had slowed a touch leading to more errors, but his back-arching serve still helped him to the upset, his best win of the year. Yet in the next round, he lost to emerging Russian youngster Evgeny Korolev, a player many have likened to a young Safin.

"I would have loved to win in Moscow at least once," Safin said. " 'Is it disappointing?' Yes. I am not perfect and neither was my career. In the end tennis is like life, messy."

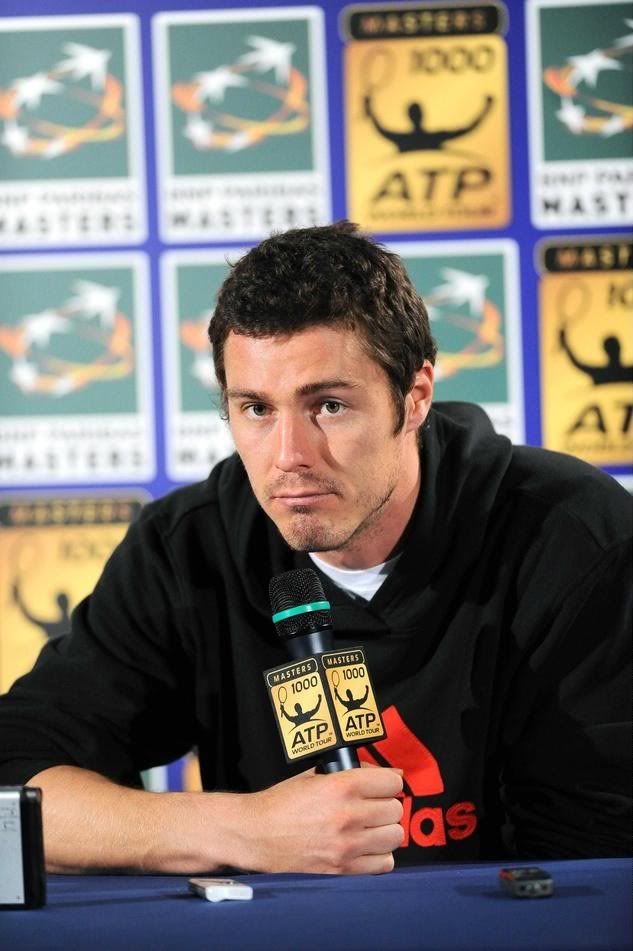

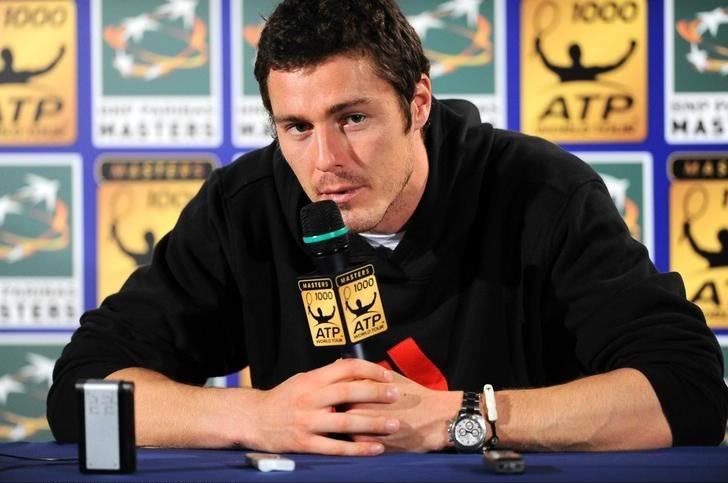

After his loss to Korolev, Safin made good on his promise to show me around Moscow. I was hanging out with ATP World Tour doubles player Ross Hutchins, and agent Allon Khakshouri in the player's lounge when Marat walked in, showered and changed after doing his post match press conference. We all piled into his Porsche Turbo Cayenne and Marat navigated the traffic-packed streets like an experienced city driver. Our first stop was Marat's beautiful, newly refurbished penthouse apartment in the heart of Moscow. The apartment was straight out of an episode of Cribs. What was even more impressive than the home was the satisfaction and detail Marat took in giving us our tour.

The home was obviously littered with the normal tennis player paraphernalia, tennis racquets strewn all over the place, and boxes and bags of adidas clothing, all demonstrations of a life lived out of a suitcase. There were plenty of symbols of his Hall of Fame career: the US Open, Australian Open, and Davis Cup trophies, pictures with royalty, and other photos capturing unique moments in time, but it was the warmth of the home that showed the true humanity of the owner. Marat took great pride in not just the home but also the effort he had gone to decorate it in his unique style. One piece of furniture in particular, a one-of-a-kind hand-carved table from the bark of a very large tree was spectacular. After a few celebratory toasts of Russian "milk" (meaning Vodka) the group jumped into some cabs and proceeded to have an extremely memorable evening.

Safin's anger and frustration was most often a result of his perfectionist approach not just to tennis, but also to life. It has been well documented that Safin regularly broke tennis racquets when frustrated, snapping them as easily as if they were pencils. "One year I probably broke about 50, but luckily I get them for free," he says. One year after a loss at the Open 13 in Marseille, Safin took out his frustration on the locker room, wallpapering it with racquet shrapnel. His response to bemused bystanders was, "Bad day!"

Like most people Safin's flaws were also his strengths. In a technical sport like tennis it takes nearly a million repetitions of a stroke to gain mastery over it, thus it takes tireless work and intensity to become successful. It is a misconception that Safin cared too little about his tennis; when in actuality it was his desire to master it that often impeded his progress. "I am a perfectionist. I always wanted to master the sport, but tennis is a sport that you can't be perfect at. You learn more from your mistakes, and as a result you become stronger. Sometimes it was my mind, other times injuries and my body, but at the end I accept I am what I am. Tennis gave me everything I have in my life, so I am very thankful to the sport and I hope to find a way to stay involved in it in someway."

Safin's critics will be quick to point out that after winning the 2000 US Open it took Safin four years to win just one more Grand Slam

"My career was definitely a roller coaster, but so many times when I was playing my best I got hurt." Safin had major knee and wrist surgeries in his career that thwarted momentum, but there is no doubt that his ability to process pressure and manage the temptations his success created played a part in his inconsistency. The 2002 Australian Open final against Thomas Johansson was a symbol of Safin's struggles. Playing with all the pressure of being a huge favourite against a first Grand Slam final participant, Safin played a tentative and emotionally erratic final. The only story that garnered more attention then the loss was that of the three provocatively-dressed women cheering Safin on from his player's box.

Although he clearly marches to the beat of his own drum, Safin said that his flamboyance should not be mistaken for lack of professionalism. "I live for myself, I don't need other people's judgments. People think I party every night, and it is insulting."

"In tennis you are all alone, fully exposed, there is no hiding." You can say what you want about Safin but unlike most elite athletes and entertainers there is freshness in the ownership he takes over his actions.

Sipping a coffee at a Cincinnati Starbucks in August, Safin discussed his looming retirement, "I just can't do it anymore, the hotels, the flights, the same people, practising day after the day the same things, a million tennis balls. I am not like Nadal where all I think about is tennis, it is time for something else. One of the problems with being a tennis player is there is no time for anything except tennis. The pressure is there all the time, no opportunity to learn or explore other interests. That is what I am looking forward to the most, the freedom. I know my second life will be much different than my first, but I am excited to see what else I can accomplish.

"I don't want to be one of these athletes that just sits around and doesn't do anything. I plan to take about six months away from everything to regroup, and then start thinking about the next phase of my life."